At the Eastern foot of the Rocky mountains in Wyoming sits the town of Cheyenne, home to about sixty thousand people. Founded shortly after the civil war, its stereotype is one of hard-working middle-America. But if you take Highway 210 to the outskirts of town, you’ll find an inhabitant that redefines the concept of hard work: the fortieth most powerful supercomputer in the world.

Cheyenne was ranked as the 40th most powerful supercomputer in the world by TOP500 in June 2019.

The eponymous “Cheyenne” is maintained by the US National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), and is almost exclusively used for running computer models of the climate system. Cheyenne is mostly controlled remotely via the internet by scientists in Boulder, Colorado, and often from the iconic Mesa Lab which overlooks the city from a picturesque mountain plateau. I was invited to the Mesa Lab for two weeks to learn about NCAR’s in-house climate model and run it on Cheyenne to study the polar climate system.

The Mesa Lab sits on a small plateau at the foot of the Rocky Mountains looking over Boulder

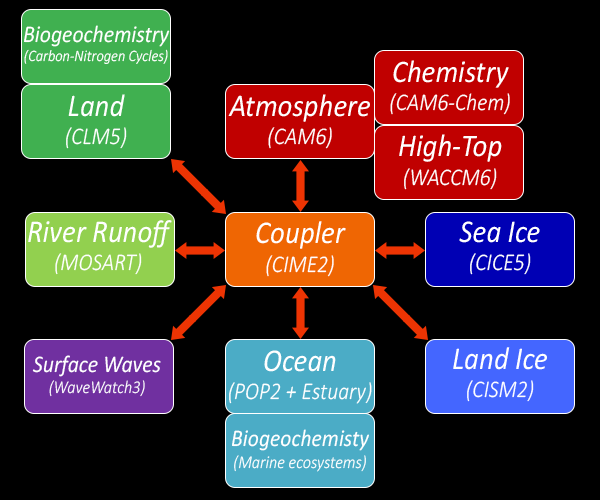

Modern study of the climate depends on modeling the different systems that define it (such as sea ice, forests and ocean biology). Climate scientists now talk about “earth system” models rather than just ‘climate models’ to reflect this complexity. My first week in Boulder would be dedicated to exploring one of these earth system models: CESM (the Community Earth System Model). CESM simulates seven systems and their interactions in around two million lines of code.

The case of full coupling between atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, land ice, waves and the land surface is extremely computationally expensive and rarely run by specialist groups such as mine at the Center for Polar Observation and Modelling. Instead, fully coupled runs are carried out centrally on supercomputers like Cheyenne and the results are uploaded onto online archives for analysis.

Schematic of the earth systems coupled together in CICE v2

Rather than run CESM in “fully coupled” mode, most scientists run simplified “cases” of the model to study specific systems. For instance, you may not need to compute the distribution of ocean waves in a study of how volcanic eruptions affect ozone production in the upper atmosphere. In the first week I became familiar with running these simplified cases and examining the output. The mornings were generally taken up by lectures from expert modelers, and afternoons were spent running CESM in different configurations and with different settings.

Keith Oleson helps tutorial students run CESM. Photo: @NCAR_CGD

Week two was dedicated to modeling the polar climate system, and the attendees were reduced from around 80 to 20. We began week two by forming teams and making predictions for this year’s minimum area of Arctic sea ice. The week then ran with a similar format to the first. Exercises now included modifying the source code and running the model at different complexity levels to deduce the behavior of individual systems.

In the evenings we made the most of the Mesa Lab’s dramatic geography, hiking the mountains above us and walking back into town for late dinners. The generous per diem from the workshop’s organisers allowed us to eat out together most nights, discussing science and a lot else. During the middle weekend, some of us rented a car for more ambitious hikes and experienced Boulder’s wildly changeable weather first hand. One social highlight was being kindly invited to Marika Holland’s house for an evening of empanadas, conversation and corn-hole (British readers should google it).

An opportunistic evening hike up the Bear Creek trail. Photo: Adi Nalam

Over the fortnight I went from a total climate modeling novice to a confident user of CESM. Looking at the notes I took, I can now happily modify the source code, design my own model runs and process the output. More broadly, I have a much better understanding of nuanced but important concepts like the role of internal variability and model hierarchies. What’s more, I made lots of great contacts with sea ice scientists and polar modelers and have plans to do some cool stuff with them in the near future!

As well as the course being free, my flights, accommodation and per diem were generously funded by NCAR and its Polar Climate Working Group, which are in turn sponsored by the US National Science Foundation.

NCAR 2019 Polar Modeling Workshop participants and organizers. Photo: David Bailey/ Todd Amodeo